STARTING OUT

JC: In 1965 my mother bought me a Sony 7″ reel-to-reel tape recorder. It was mono, with one microphone. I’m not even sure why I wanted it. I soon became bored just recording my favorite records and began recording sound effects. Then I got bored with that and discovered if I put a band-aid over the erase head, I could create a sound on sound recording. I would record records at different speeds; sometimes backwards, people talking, stuff off the TV, until the 1/2 hour reel was full. If I kept doing layer upon layer, I would get this garbled collage of sound. Mind you, I couldn’t hear what was previously recorded because when I put the recorder into record the speakers would shut off. It was always a surprise. Years later my friends and I would sit around at night smoking pot and play the tapes. Hey, it was 1968…

AW: Did you play an instrument?

JC: I played the drums from the age of 15 until I was around 30. When I couldn’t play in a band and engineer at the same time I stopped playing professionally.

AW: What kind of music did you play?

JC: I was into rock and played in a band called the Rockets in 1972. Eddie Mahonie was our lead singer before he became Eddie Money. We had a big following in the Bay Area that eventually attracted an engineer by the name of Tom Lubin from CBS studios in San Francisco. Tom arranged for the band to record at his friend’s studio in Ojai, California.

AW: Was this your first recording studio experience?

JC: Not exactly, we did a recording in a small studio in San Francisco’s Chinatown district a year earlier. They wouldn’t let us into the control room. When we stopped playing they handed us a reel-to-reel tape in a white box and asked us to leave. I think we were too loud.

AW: When did the recording engineer bug start to bite you?

JC: In Ojai, working on the Rockets recordings. It was a loose atmosphere and they let us fool around with the equipment and do some mixing. When the Rockets broke up a year later, the owner of the studio hired me as a caretaker/intern for a studio they were trying to build in the mountains above Santa Barbara. I moved there hoping I would someday be the chief engineer making tons of money and hanging out by the pool with famous rock stars.

AW: And the reality was…

JC: Well, the studio was never built because the land was actually in a National Forest and after a year they ran out of money fighting all the legal roadblocks. I went back home to the Bay Area and started over. But I knew I wanted to be a recording engineer and I took whatever job I could get in the business to pay my bills. I road-managed a band for Elektra Asylum records for a year. I helped build a touring PA company with some friends of mine that specialized in “on-stage monitor mixing,” a big new thing in late 70’s. I eventually landed a gig with Stevie Wonder mixing monitors but I still wanted to get into the studio. By now I was the father of a three-year-old girl and the pressure was building to make it happen.

AW: What were the circumstances surrounding your first recording experiences?

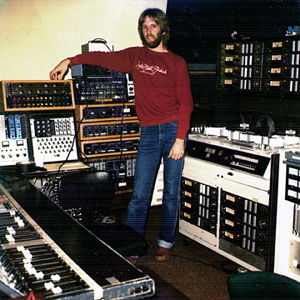

JC: In the late 70’s, if you wanted to be a studio engineer you had to know someone at a studio and work your way up the pecking order or build your own studio. But you couldn’t go to a store and buy a studio like to can today. You instead had to find used gear and then fix most of it. My good friend Dan Alexander, the former guitar player in the Rockets, was a vintage guitar dealer at the time. He too wanted a studio so he turned his attention to finding used recording equipment. He eventually amassed enough gear to outfit a 16- track studio that had a tape recorder the size of a small car. It was there, in a converted mom and pop grocery store he called Tewksbury that I recorded my first record, for a Jamaican reggae band called Soul Syndicate. It was also there I met and recorded the Dead Kennedys and Joe Satriani’s pop band, The Squares. But I was still doing live sound and playing drums to make ends meet. It was very hard and I was beginning to question my future as a recording engineer. It wasn’t until 1987, when I recorded Joe Satriani’s “Surfing with the Alien,” that I began to actually do better than just survive. That record attracted a lot of attention and received a Grammy nomination. I started getting calls from record labels to do other guitar bands, mostly speed metal and punk stuff.

ON the DEAD KENNDEYS and PREPAREDNESS

JC: I was an employee at Hyde Street Studios in San Francisco in 1980 and was asked to engineer the Dead Kennedys second full-length album with Thom Wilson as the producer. After about a week of recording they had a falling out with Thom. They kept me on to engineer and the band finished the record they titled “Plastic Surgery Disasters”.

AW: Where they difficult to work with?

JC: No, at that point I had established a relationship with them. They could trust me to oversee the recording. But it was like riding a wild horse. They were a really good live band. Essentially the records were recorded live. The vocals were overdubbed, and some of the guitar parts were added later. It was not a crazy, drugged-out event. It was more of a deliberate, professional approach.

AW: You were still pretty new to studio engineering..

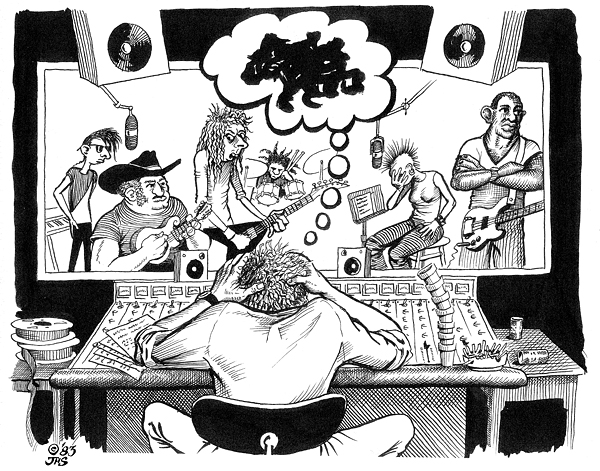

JC: Defi?nitely, I was just learning how to be a recording engineer, and I had to learn how to work quickly and set my priorities. Early on I tended to spend too much time with details that would get in the way of the performance. It’s a mistake a lot of new engineers make. If I’ve got a band who’s ready to record and the energy is up in the room, I shouldn’t spend the next two hours listening to a snare drum or trying to find a better place to put a microphone on a speaker. The idea is to get in there and to capture what they’re doing… so they come in, set up and the tape better be rolling. But what if I didn’t spend time getting good drum sounds or putting the bass in a good place for isolation where it wouldn’t leak all over the drums? To work fast I had to learn how to fix or cover up my mistakes later on. As I made more and more records I learned what and what not to do. I would fall back on things I knew would work. All experienced engineers do this. They fall back to a bottom line of skills that guarantees a good recording. In situations like this, or in live situations, it’s invaluable. You’ve gotta be able to know you can put a Shure SM-57 on the snare in *this* position, record it flat, and be guaranteed something you can work with later. As opposed to: “Well, gee, today let’s try this old tube mic cause I read in a magazine that so and so uses a it.”

AW: You knew the DKs were ready to play and you had a limited amount of time. How did you go about it?

JC: I treated them like a live band. If you were doing live sound at a concert, you do the tried and true. You use gear you can rely on. At the time we were using a nice sounding all discreet Trident B series console [Ed note: the console with which Queen recorded “Night At The Opera”]. I just didn’t do anything that would be too artsy. It didn’t require the recording engineer to take risks that might interfere with their performances. I wasn’t that conï¬?dent in my own skills to want to try and make a “great” recording. It was more incumbent on me to document the event. Later on I took more creative liberties.

AW: Like with the Joe Satriani recordings?

JC: Yes, and the next DKs album, “Frankenchrist”. As I built up my confidence I started experimenting more with mic placements, effects and tape editing.

AW: Did you use these experiments to develop your own sound?

JC: Not at all, if you listen to “Surfing With The Alien” and then “Frankenchrist,” there’s nothing similar in the way they sound. I always took great pride in not having a “sound” as an engineer. Satriani had a sound and the Dead Kennedys had a sound, and it’s my obligation to present that to the world – to document what it was they’re doing. My role with the DKs was very different than it was with Joe. Joe was much more methodical, much more experimental. We had the time and luxury for me to try five different microphones on an instrument and to experiment with arrangements and recording techniques. But the DKs unstated goal wasn’t to sound like other punk bands at the time – very in your face, very dry and aggressive sounding. The Dead Kennedys wanted something different. Ray, the guitar player, used a Fender 12-string and a lot of tape delay, an Echoplex, so he was already shaping the sound of the band. Hyde Street had some really wonderful sounding live echo chambers. I could go in there and move the mic and the speaker around and experiment. I started using reverbs with the Dead Kennedys and they liked it – a lot – and they wanted more and more. Pretty soon “Frankenchrist” turned into a roar of reverbs that created a sound no one had done before on a punk record. But when we did the next record, “Bedtime For Democracy,” we got self-conscious and I was forced to pull back on it which I think now was a mistake. I believe “Frankenchrist” established a sonic landscape for the band that wasn’t followed up by “Bedtime.” It was starting to sound more like classic rock production, where you’d use reverbs discriminately.

AW: Was that a decision they left up to you?

JC: I’m not sure exactly how it came about. Maybe our sensibilities kicked in. When we were making “Frankenchrist” it was more the lack of experience and not being inhibited; maybe not being concerned about what we were doing and just doing what it was we wanted to do. Making a record we liked. Many hardcore fans wanted conformity in their punk records and didn’t like the reverb. I think we were getting a bit worried.

ON JOE SATRIANI and the ENGINEER/PRODUCER CONUNDRUM

JC: I think of myself as a recording engineer. I’ve never been comfortable with the title of producer. The first person to call me a producer was Satriani, after the success of “Surfing With The Alien.” He said: “I’m going to give you co-producing credit on that and ‘Not Of This Earth’ as well,” and I was shocked cause I’d never thought of myself as a producer. I mean: a producer; that’s George Martin, Quincy Jones, Daniel Lanois. They’re producers. They can produce music. They can go into a room, pick up an instrument and produce music. I’m a recording engineer. I love the art of recording.

AW: You’re the first person I’ve heard actually use the phrase “music producer” literally…

JC: To me it just makes sense. I’ve been around producers who can stop the band in the middle of a take and say: “Rather than going to the A there, go to an A minor and let’s hear how that sounds.” I would never do that! I might say, “You know, I want to try a different mic on you,” something technical. With the Satriani records it was more challenging, I had to create a sound field for his guitar to reside in, something unique. I was given, within reason, as much time as I needed to experiment. I also helped Joe pick takes, sequence the record, and I would often choose the studios and book the sessions. My role as engineer slowly expanded as he trusted me more.

AW: Did he invite you into these responsibilities? Did you seek them out?

JC: When we first started working together he had little studio experience. By then I was already involved with a recording studio so I knew a little. So when myself and the Squares (Joe’s pop trio, pre-solo career) started recording, we learned together. They were figuring out how to arrange and produce their music and I was learning how to record it, so we grew up together. By the time Joe went solo 3 years later, we had studio experiences behind us. There were certain things he would leave up to me. He wasn’t particularly interested in how we got there because he was so totally focused on playing.

AW: How did the two of you meet?

JC: I met the Squares, and Joe Satriani specifically, at their first gig. They were opening for Greg Kihn. I was mixing on-stage monitors. I think it was their manager who came up to me and said: “We don’t have anyone to mix our set. It’s important to us, it’s a big crowd here (Greg was selling these clubs out), we’re opening, we’re from Berkeley, you’re from Berkeley, will you help us out?” I said “Well, sure.” So they come out, Joe plugs in and starts playing, and I was floored. After the set I went backstage and I said to Joe: “I don’t know who you are, or what your band is doing, but I want to get you guys in the studio.” That simple offer changed my life. We did almost three albums worth of material. When Joe decided to go solo he called me and said, “I wanna make a solo guitar instrumental record. I just got this credit card, the limit is $3500.” A few weeks later Joe’s “Not Of This Earth” album was done.

ON MENTORING

JC: Recording is nonstop problem solving. There’s always a problem, from the moment the artist walks into the studio all the way to the mastering session. My ability to solve problems comes only through experience. I can’t pull a manual out and figure out how to fix something, at least not quickly and with any integrity. In the early days I would over-prepare. I’d get to the studio before everyone, set everything up, check everything – every microphone, every cable – I’d minimize the amount of potential problems. But as soon as the band rolls in there are problems anyway. So many problems you can barely deal with it. AW. Good thing you handled the nuts and bolts first…

JC: Yes. I learned early on, because I came from a live sound background, that I needed to be prepared or I’d get burned. As I made more records, I gained skills and confidence that I’d apply to the next session. I eventually built a bag of tricks. Now when I go into a session I’m not worried. There’s no problem in a recording session that I haven’t been through 10 times. You can throw all the computer crap in there, too. In fact it’s funny now with computers, my reaction to computer crashes; lost data, frozen computers, all of that stuff. I’m not affected by it. Some of the younger kids who have grown up making records with computers, it’s something they’re afraid of. In the old days it was me punching in at the wrong place and erasing the end of a guitar solo. I couldn’t ever get it back. You face your mistake, you deal with it, and you move on. Now they’ll sit in front of the computer for four or five hours trying to get it back or repair it and I’m thinking: “Let’s just do it again…get your guitar on, go out there, we’ll do it again.”

AW: Sounds like you’re talking about a whole generation of younger engineers that don’t have a hard-knock analog background. But human nature doesn’t change. What’s the difference between then and now?

JC: The difference is there’s no mentoring.

AW: Was there for you?

JC: Some, but no formal training. When I started in the early ’70s, if you wanted to be a recording engineer, you needed to get into a recording studio. The studios were primarily owned by record companies. I was in the first generation of engineers circumventing that system. Independent recording studios were appearing. But there were no schools or books on the subject. Occasionally we could talk a real recording engineer into teaching us how to align a tape recorder, edit tape, or show us how to use microphones.

AW: Is there any mentoring nowadays?

JC: I imagine in some of the better recording schools you will find experienced “old school” engineers teaching what they know. An assistant engineer at a high-end studio may learn a few tricks from the engineers and producers they come in contact with. But for all the project studio engineers – they’re on their own to read manuals, magazines and make mistakes.

AW: But so did you…

JC: Sure, but I really miss the fact that someone didn’t mentor me through the studio system like a Roy Halee or Tom Dowd. I was very fortunate to have access to a small recording studio, so I could figure it out myself but it would’ve been great to have a real teacher.

AW: How does someone with a project studio get formal training?

JC: Most don’t and that’s a problem. Some with natural abilities figure it out sooner or later. But at some point no matter how good they think they are, they’ll need to be tested outside their controlled environment. Being able to walk into a recording studio anywhere in the world and take control of a session is a daunting task. To make a living as a recording engineer this is required. You can’t expect that every client wants to work at your place. You need to get out and work at other studios.

AW: Do you recommend being an intern at a commercial studio?

JC: Yes, if the intern takes advantage of it. I’ve seen some interns go from mopping floors to second engineer, to first engineer in less than two years. It’s rare but it happens. Others never take advantage of open time in the studio, asking questions or seeking help from other engineers. Some seem happy just doing simple tasks and then disappear after a few months. I think the experience demystifies the hype around show business… you know: somebody famous screams at them for bringing the wrong kind of potato chips!

ON DIGITAL vs. ANALOG and CHEATING

AW: Okay, here we go: digital vs. analog…

JC: With computers, with all the manipulation, the editing, pitching and multiple takes – you can make a marginal record into a good record, but you can’t make a good record into a great record. I’m aggravated to see people sing for 30 minutes and then spend three hours at the computer editing, pitching and comping. It happens more than you think. Have you heard the joke? “What did the ProTools engineer tell the singer after the first take? “That was crap. Come on in.” I think people rely too much on computers and not enough on getting good performances. When I first started you had to perform it. You couldn’t fix it. You could do it over and over again but you would get to a point of diminishing returns, and you better have kept the stuff that was good. Digital manipulation has created an entire genre of music that is, in a way, dishonest. I use the word “dishonest” because when you hear a song on the radio now, you don’t know what you’re listening to. You can’t tell whether or not they sang that in one take and they’re good singers, or if they spent six months fixing it digitally. You don’t know if the drums have all been cut and timed and repositioned, or if the drummer is really good.

AW: Is that kind of dishonesty a bad thing if the record is good? If the fans are happy and they can pull it off live?

JC: I think the ultimate test is when you go see the band perform live. Does the end justify the means? I suppose. But I think the artists are selling themselves short. If they could perform it themselves, with little or no manipulation, they’d be happier with themselves. They’d be more proud of what they’re doing. They could listen to their CD and know that *they* did that, not a computer. It would also create more subtle differences in the bands’ overall sound. It bothers me because it takes something away that I look for in music. The frailty and spontaneity of a human being, the intimate relationship with the performer is gone. There seems to be a wall between the listener and the recording artist, due to computer manipulation, that didn’t exist before.

AW: Do you think listeners aren’t aware of the manipulation…

JC: Inherently they know that musical performances are never perfect. I think listeners prefer some nuanced imperfection in the music.

AW: So part of your responsibility as a recording engineer is to make a judgment call. You judge whether to manipulate what you have, or have the musician do it again.

JC: It has a lot to do with how high you have placed the bar on performance and what the expectations are. For instance, if the drums and bass are spot-on due to digital editing it forces the other players to also be spot on. So what happens is all the attention goes to making a “perfect” record. This can take forever if the players are marginally talented and the editor has limited chops. What they most often end up with is a strange-feeling recording that listeners don’t respond well to. They’d be better off rehearsing for a month and cutting the tracks live in the studio.

ON REPUTATION

JC: My reputation is all I really have. Artists I work with come and go, and what they bring to me musically affects what I put out. I have a reputation for not interfering with that process. A lot of people don’t agree with this philosophy. A lot of engineers get intimately involved in all aspects of a recording. They get involved in areas of the music I wouldn’t because they see themselves more as producers. The role of a recording engineer has smeared into the function of writer and performer and producer. I’ve always drawn the line. I wouldn’t be in a room with these people if I didn’t think they could sing, write or play. So why am I gonna get involved with any of that? As a recording engineer, if I’ve got everything taken care of technically, if I’ve got a good assistant, I can relax and give them the greatest gift of all which is to let them know when I’ve captured something great, or when they need to try it again. That’s a role that crosses into production. At that point you’re acting like a producer in one way. I think that’s why on a lot of records I make I’m given credit as co- producer. But I don’t see myself as a record producer, I see myself as a facilitator. If a label is so excited about this band that they’re going to put up the money to get them in a studio then it’s on me to capture it, not reinvent it.

What Makes A Good Recording Engineer:

For Tape-Op Magazine

Here’s 20 suggestions in no peculiar order. Some I learned the hard way.

- Be humble. It’s a great job if you can get it. You’ll never know everything.

- Attention to detail. It’s the little things that make or break you.

- Always admit a mistake and be willing to make it right no matter how much it hurts.

- Before you begin a project make certain the artist understands your role and responsibility. All too often engineers cross the line into producing without knowing it. Before long you may be wishing you were “just” the engineer.

- Be in command of your domain. The artist needs to feel con�dent that you can operate all this fancy equipment so they can concentrate on what they need to do.

- Allocate responsibility when appropriate. No one expects you to do everything. If an assistant can do something for you so you can concentrate on more pressing matters that’s okay. Don’t ask an assistant to do a task you should be doing. Work as a team with your assistant – they’ll watch your back for potential disasters, especially if you’re getting tired.

- Never talk politics with a recording artist. You never know where they’re at on any certain issue and some may take it very seriously. Why go there? You have enough problems.

- Never get stoned during a session even if the artist offers it to you. If you make a mistake later it was because you’re a stoner. No a way to start a career.

- Don’t blame the equipment. Everyone understands that equipment can fail from time to time. An engineer who is always complaining is a downer for the performers. Shut up and work around it, you’re a professional.

- It’s your job to make sure you get the proper credit in the liner notes. Don’t leave it up to a band member or assume the record label will take care of you.

- Never do a “spec” project unless you are willing to do it for free.

- Learn to accept the word “no” and move on. You will hear it a lot when looking for a job. There is some luck involved but you can make your own luck.

- In the beginning say, “yes” to any job offered in the music business. You never know who you’ll meet or opportunities that may come from it.

- Never loose your cool. Someone has to keep it together in the studio.

- Don’t allow the artist to keep you in a session longer than you can handle. Long hours don’t beneï¬?t anyone; you’re likely to make a mistake.

- If you don’t play an instrument; start now. It will help you relate to musicians and their equipment better.

- If you get a job at a studio it’s your obligation to protect their best interest, report any problems to the manager or owner and make the studio look good.

- Keep the equipment and yourself clean at all times. Dirty equipment is a bad sign. A dirty engineer is even worse.

- Performance is everything, sound is secondary. Spending time on headphone mixes is better time spent than listening to a kick drum for an hour.

- When an artist is performing they may be reading your face through the glass for reaction. Always be conscious of what your face is saying.